11.06.2007

I. Zaitsev. THE PHILOSOPHY OF STRATEGY (Part 2)

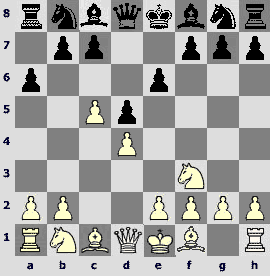

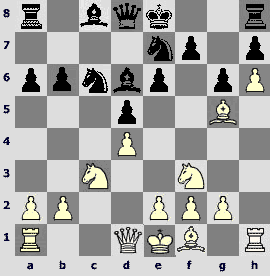

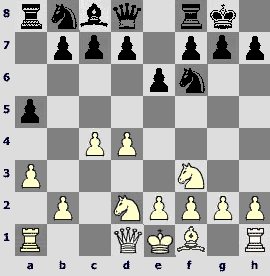

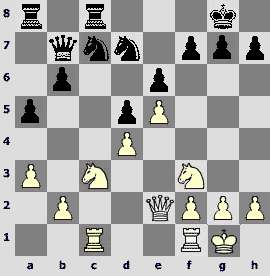

During the last one and a half centuries the process of qualitative improvement of the chess substantial part has been on the ascent all the time, and now none of the examples from classic arsenal seems to meet modern requirements. And this is no wonder, as the chess space is as limitless as the universal one. As far back as in 1950s Mikhail Tal has foretold prophetically that a manned flight to the Moon would happen much sooner than a faultless chess game. Let us take as an example the beginning of the game between two historic celebrities. This can give us some notion of how rapidly the changes of strategy happen. Queen's Gambit A. Alekhine – A. Rubinstein The Hague 1921. 1.d4 d5 2.¤f3 e6 3.c4 a6 This variation is rare enough now. The first one to introduce it into practice in the version 3.¤с3 а6 was David Janowski, and Oldrich Duras began to employ this advance as a reply on 3.¤f3 as well. This variation, on the one hand, provides White with ample opportunity to transpose into the Carlsbad, Meran or Catalan setups, but on the other hand the threat of immediate capture 4...dc4 blocks the road to orthodox Јueen's Gambit in its usual version for him. Of course, we can let our imagination run away with "refuting" the variation by way of 4.Ґg5!? f6 (after 4...¤f6 White still forces his way to advantageous enough variations of the Јueen's Gambit Declined). Then (without excessively detailed elaboration) the following series of moves can be seen: 5.Ґh4 dc4 6.e3 b5 7.¤e5 Ґb4+ 8.¤c3 Јd5 9.Јg4 g6 10.¤:g6 hg (after 10...¤h6 11.Јg3 hg 12.Ј:g6+ ¤f7 13.Ґ:f6 ¦f8 14.Ґg7 even computer is ready to admit its own failure) 11.Ј:g6+ ўf8 12.Ґ:f6 ¤:f6 13.Ј:f6+ ўg8 and White chooses between giving a perpetuate check and procrastinating with a draw by playing 13.Ґе2. Our only aim for giving this most relative variation is to show that a modern player who is critically disposed to the prevalent standards, should be able, while working on an opening position and being aware of his analytical powers supported by the computer, to touch many different strings in it. 4.с5 Here is the first exercise for you to show off before the classics during discussing the strategy. According to general conceptions the active party, having relieved the tension in the center on this stage, refuses to employ its seemingly main "trump" voluntarily. As modern strategy sees it, this would retain the prospects for keeping an advantage only in case of White having some prerequisites for conducting his operations on any flank. This is the reason for this questionable line failing to take root in theory and being only of minimal topicality now. This position has been surely examined by the future fourth world champion and one of the best analysts of his time at home, but still he chooses 4.с5.Today such a strategic decision is hardly acceptable even for a player of average skill. This example alone serves to me as a proof enough to show that the radical changes in our perception of chess position relate first of all to the department of strategy. (Still, as I have already noticed, to lay the blame for this on our predecessors would be like reproaching Strabo for the lack of information on the Suez Canal in his "Geography"). If you are not convinced yet I suggest that we turn to another recurrence of the similar strategy that has taken place in later times in practice of another world champion. Probably everyone remembers the game M. Botvinnik – G. Ilivitsky played in the 22nd USSR championship: 1.d4 ¤f6 2.c4 g6 3.Ґg5 d5 4.¤c3 ¤e4 5.Ґf4 ¤:c3 6.bc Ґg7 7.¤f3 0-0, and here Botvinnik, to great surprise of many, played 8.с4-с5?! Chess world always stands a particularly vigilant guard over its strategic axioms. Such mistakes are the most fatal in its consequences, as, being made on the level of general principles, they program a wrong strategy for the future. In spite of the fact that the colleagues should be quite lenient to the unsuccessful chess experiment of the world champion who had carried great and well-earned authority with them and had been held in high respect, still such a continuation devoid of any strategic principles or ideas (it is just plain impossible to suggest now that this has been a result of home analysis!), had met with a practically general condemnation in the chess environment even then (remember, it was still 1955!). Summing up the results of the championship P. Romanovsky wrote: "Has Botvinnik really thought that after 8...b6 9.cb ab his position becomes stronger...? Why had not White simply played 8.е3? It is impossible to understand the world champion's motives in this case..." So it turns out that as far back as half a century ago his country has already lived under conditions of universal strategic literacy! 4...¤с6 (Later while playing this position as Black already the forth world champion had tried to cut this "Gordian knot" at once – 4...b6 5.cb с5 6.¤с3 ¤d7 7.¤a4 but, although he won this game, he had failed to achieve the desired opening equality, Bogoljubow – Alekhine, the 1934 match). 5.Ґf4 ¤ge7 Of course, the problems of development can be solved without this move that, according to Alekhine, looks a bit eccentric, but Rubinstein's partiality for this position of the knights has been known to us already from the variation of the Nimzowitsch Defense. 6.¤с3 ¤g6 Isn't it possible to play in the center immediately: 6...g6 7.e3 Ґg7 8.Ґd3 f6!? 7.Ґe3!? Up to this moment we have been following the game D. Janowski – O. Duras, in which White chose 7.Ґg3 leading to equality, but here Alekhine swerves from it employing a novelty that deserves attention. Still I think that today many players would prefer a routine move 7.е3. 7...b6. 7..Ґе7 looks reliable, but 7...¤а5 is interesting as well. 8.cb сb. The idea can be modernized by venturing to suggest an interesting pawn sacrifice here – 8...¤а5!?, counting of course not only on 9.Ја4+? Ґd7!10.Ј:a5 cb, trapping the queen, but mostly on 9.bc Ј:c7. In this way Black gains a couple of tempi for his development, and, according to Tal, in the dynamic action time is most important. The calculation of variations shows that Black actually has a certain initiative for the pawn here... 9.h4! Ґd6 10.h5 ¤ge7 11.h6! g6 12.Ґg5! The exclamation marks that have been inherited by us here tell only about White's consistence in carrying out his play for taking advantage of weakened dark square complex on the K-side. This game is quite often presented as a sort of paragon for non-typical concrete play. White's actions were indeed original, but due to the fact that he had been carrying out a disputable plan, wholly abandoning the strategic influence on the opponent's central structure, this should have lead to the loss of the first-move advantage. Objective analysis shows that it would, in all probability, have happen exactly that way, should Black make the only, in our opinion, precise move here - 12...f5. To Alekhine's credit be it said that he admits that he has not been himself in this game. Although he had soon managed to gain great advantage and convert it into a win brilliantly, the worm of doubt about the fairness of this result seemed to give him no rest. But you should not think that the c4-с5 strategic advance is wrong in all the cases. That is not so; it is just that some favorable attendant factors are just needed in order to fill it with certain meaning. As an example I dare to suggest to the readers one of my own games. I. Zaitsev - M. Taimanov Furman Memorial, St. Petersburg 1995. 1.d4 ¤f6 2.c4 e6 3.¤f3 Ґb4+ 4.Ґd2 a5 5.a3 Ґ:d2 6.¤b:d2 O-O. 7.с4-с5!? A little opening novelty that has been found during the game. As Black's Q-side has been weakened by а7- а5, this continuation leads to White's spatial advantage here. 7...b6 8.cbcb 9.e4 d5 10.e5 ¤fd7 11.¦с1 Ґа6 12.Ґ:a6 ¤:a6 13.Је2 Јb8 14.O –O ¦с8 15.¤b1 Јb7 16. ¤c3 ¤c7 and after 17.¦с2 followed by ¦fc1 White retains his positional advantage. It is exactly the strategic newness exceeding the habitual limits that is always revolutionary in its character as it is connected with overcoming certain canonical conceptions. It is already no short-living sensation but something more than that, it is a little chess miracle in its essence. By virtue of that it has its inherent "exterritorial right": many generally accepted positional laws do not apply to it. Still in the final analysis that does not lead to a rejection (he who rejects the past does not have the future) but only to a deeper understanding of the principle itself. In the middle of the last century everybody knew perfectly well that the epoch of "great geographic discoveries" in chess had been left far behind. All the principal continents and archipelagoes had already been marked on the chess openings' map. And if another chess revolution was bound to happen, than on what foundations would its energy – not necessary destructive, but certainly critical – be directed? Obviously it would have to clear the way for certain latently accumulating but not yet formalized new conceptions. Thus, we have now learned not to see in the "Hedgehog" paradox just a neglect of the spatial advantage but to take into account its finer and more precise interpretation, when not the scale of a "sham" territory is brought to the forefront, but a structured organized board room notable for its harmonious control over the vitally important squares or points. The meaning that had been attached to the concept of positional weakness, be it a square, a point or a pawn, in the beginning of the last century was also changed by constant improving. It became obvious that every object on the chessboard, including any doomed pawn, besides its statistical significance has also a dynamic component that is often not taken into account. The play in many a modern defense is based on rejection of a fatally unambiguous role of a weakness, even on its being, in a sense, illusory. A century ago in medicine they used to implant pieces of shark's fin into a human organism. It was thought that, while dying, those tissues emit a great lot of health-giving bio-energy. On similar, though purely formal, resemblance to a live-activity surge after a material loss counterplay of a defending party is based not only in gambits, where a pawn is given up willingly and at once, but in many modern systems as well, in which that pawn is lost gradually and reluctantly. The striking example of this is the Cheliabinsk Variation of the Sicilian Defense that seems to be just "stuffed" with superficial positional defects. It would be hardly approved by specialists should it appear on the chess scene any earlier than in the middle of the last century. But the variation, as they say now, turned up "just in time and in the right place" (as far as I remember the first game in the modern version of this variation was played in the USSR in 1965). The second opening revolution, having stated as its guiding line a drastic growth of a part played in the game by dynamic and technical means, was already starting its impetuous run by that time. An obvious source of this powerful reformatory process can be considered a famous post-World War II the USSR against the USA radio match, when the Soviet team has brought down on their opponents an opening preparation system of the latest pattern (see the games Denker – Botvinnik and Smyslov – Reshevsky). During the following three decades the number of the tournaments had grown sharply; as a consequence the number of GMs also increased many times. This alone testified to the significant widening of the circle of the chess pros. There came globalization of the chess information exchange process (the complete indexing system, quick publishing of collected tournament games, informants and encyclopaedias etc.) Theorists of the world have unanimously taken for granted the unwritten rule according to which an advantage in chess changes strictly in the limits of some hard parameters; this had a beneficial effect on the objectivity and quality of opening analyses. They begin to grow broader and deeper, extending over greater areas, and that inevitably led to disappearance of the borders between the opening and other stages of the chess game. In the long run all this couldn't but lead to the revision of many propositions of the existing strategy. But there happened to be no adequate ending that would have summarized philosophically the results of the whole process. There is a impression that by the time the powerful computer programs appeared the ideological chess (mostly opening) revolution still had not managed to put the principles of the modern strategy into a theoretically valid shape, and so it was left unfinished as if cut short. That is why we have inherited so many blank spots from last century's opening theory, and the number of the unsolved opening problems tends to grow now. Sometimes, looking at the computer, you just want to cry out: "Who has opened up this Pandora's box to our misfortune!" Can we please turn it all back to the times when preparation to an important game has not taken so much efforts? But any nostalgia and reformation in those questions are counterproductive and would never be supported by a younger generation that always masters the ever-expanding information field more quickly and confidently. But, pardon me, in this case we will have to walk in circles, returning to the thought about the lack of new strategic ideas, or the game turns into a monotonous drudgery. Things has already got to the point when even during the tournaments of highest level in the Ruy Lopez d2-d3 is played more and more often – isn't it the evidence of the fact that strategic problems in many a ramification of this opening remain unsolved mostly because of the philosophic views that have become obsolete decades ago and now need renewing. This lack of adequately advanced new philosophy played its negative part on the final stage of the reforming as the previous chess philosophy had in fact surrendered to modern practice long ago. But practice devoid of the philosophical comprehension is not able to rise over the level of mere game. The "overdose" of playing practice only has lead to the situation when there is neither time nor place for the modern philosophical prologue advising of the future ways of chess development and substantiating them, as it would always happen during the previous epochs of transitional crises. All this led to the fact that the revolution that had started under the slogans of raising the dynamic significance in the absence of necessary ideologic blessings soon, under the pressure of The Computer, assumed a solely anthropogenic (or rather technogenic) character. As with the improvement and widespread application of the computers this tendency was getting much stronger, it had became obvious that the chessplayers themselves, being creative persons, lost much from the results of this purely technogenic revolution. Devouring the chaos of the virtual chess world the computer turns it into an ordered cosmos. There seems to be nothing bad in it, but actually this process limits the freedom of creative chess imagination. The well-known thesis – there is no creativity without chaos – finds another proof! Chess, while turning into more and more precise, almost mathematical model, begins to break with intuitive art. We hope that the reader has already understood the danger of this from our previous explanations. If previously a single "injection" of fresh ideas could have been enough for several decades of tournament polemics satisfying the aesthetic and creative needs of chessplayers of most different skill levels, who would be one way or another involved into a process of discovery, then nowadays, to our great regret, the circulation period of the ideas that are instantly received and digested by a computer, amounts to months or even weeks. (In fact everybody seems to work for the stuffing of one great Computer!). After that practical players have either to take routes strictly prescribed by the machine or to wait for another short burst of creative activity following the appearance of a new portion of original analytic production. Thus it turns out that an average player is banished from the boundless ocean of variations and placed into some chess oceanarium. And it is well-known that fantasy of those inhabiting a deterministic living space is quite different from one of the dwellers of immense open – the former becomes limited with time, just like their environment.

ALL ARTICLES BY AUTHOR

| I.Zaitsev. Transformation of a system |

| I. Zaitsev. THE PHILOSOPHY OF STRATEGY (Part 2) |

| I.Zaitsev. THE PHILOSOPHY OF STRATEGY (Part 1) |

Discuss in forum